Originally posted by Laura Harker at the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. Download the PDF.

People living in communities suffering from poverty are more likely to be saddled with poorer health.[1] The richest Americans enjoy a life expectancy 10 to 14 years longer than the poorest Americans, according to a study of 1.4 billion tax records between 1999 and 2014.[2] People living in poverty often face toxic stress and lack resources important to health, such as access to health care, healthy foods and stable housing. Most experts agree raising family income and helping people rise out of poverty are sound strategies to improve health.

One proven way to help alleviate poverty and create a path to better health is the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), a federal tax break that provides an income boost for working families with low or moderate wages. The credit increases as wages go up, before phasing out at higher incomes. This incentivizes work and encourages able workers to earn more. About 1 million Georgia households received the federal Earned Income Tax Credit in 2015. The tax credit helps about a quarter-million Georgians stay above the poverty line each year.

Georgia can improve people’s health by extending these poverty-reduction benefits through a state-level version of the EITC, or Georgia Work Credit. Twenty-nine states and the District of Columbia enhance the value of the federal EITC by also offering a credit that offsets state and local taxes. A refundable Georgia Work Credit set at 10 percent of the federal EITC can cut taxes by a few hundred dollars a year for eligible workers, up to around $630 per family. This offers a modest but important boost for 1 million Georgia families. It can also provide economic benefits by injecting up to $300 million into local Georgia economies.[3]

By strengthening working families and local economies, a state EITC can help improve the health of Georgians and promote health equity throughout the state. Some health benefits of a Georgia Work Credit include:

Maternal Health: Increasing EITC benefits made available to mothers with two or more children is linked to a higher likelihood of reporting excellent or very good health. Mothers who receive the credit had fewer markers of high blood pressure, high cholesterol and inflammation.[4] Higher EITCs also increased the likelihood that mothers received prenatal care, especially among black women and mothers with fewer years of education.[5]

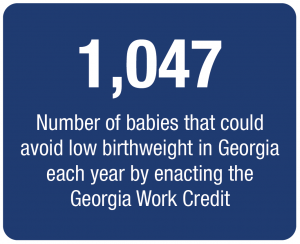

Maternal Health: Increasing EITC benefits made available to mothers with two or more children is linked to a higher likelihood of reporting excellent or very good health. Mothers who receive the credit had fewer markers of high blood pressure, high cholesterol and inflammation.[4] Higher EITCs also increased the likelihood that mothers received prenatal care, especially among black women and mothers with fewer years of education.[5]- Infant and Child Health: Babies in states with their own EITCs are born with higher average weights[6], especially when the credits are larger and families are allowed to keep the full value even if it exceeds their income tax liability.[7] A refundable credit set at 10 percent of the federal credit could result in 1,047 fewer low-weight births in Georgia each year, according to an Emory University study.[8]

- Mental Health: Higher EITCs are associated with improved mental health among mothers and children. Mothers with two or more children who receive an increased EITC refund reported fewer bad mental health days.[9] Children show fewer behavioral health problems, including anxiety and depression, for every $1,000 in tax credit their family receives.[10]

How the Georgia Work Credit Can Promote Health Equity

Extensive research highlights the EITC’s health benefits and how expanded credits can magnify them. This evidence underscores the potential health improvements if Georgia enacts a refundable state tax credit set at 10 percent of the federal credit. The health benefits can reach families across the state, especially people who experience worse health now based on where they live, their education level, or their racial/ethnic identity.

Maternal Health

Mothers receiving prenatal care

Prenatal care helps mothers maintain a healthier pregnancy and reduce risk of infant mortality and low birthweight. Although most Georgia women receive prenatal care, black women and women with less formal education are less likely to receive it at all or before the third trimester. The percentage of black mothers in Georgia who did not receive prenatal care before the third trimester is 11 percent, compared to 6.2 percent for white mothers.

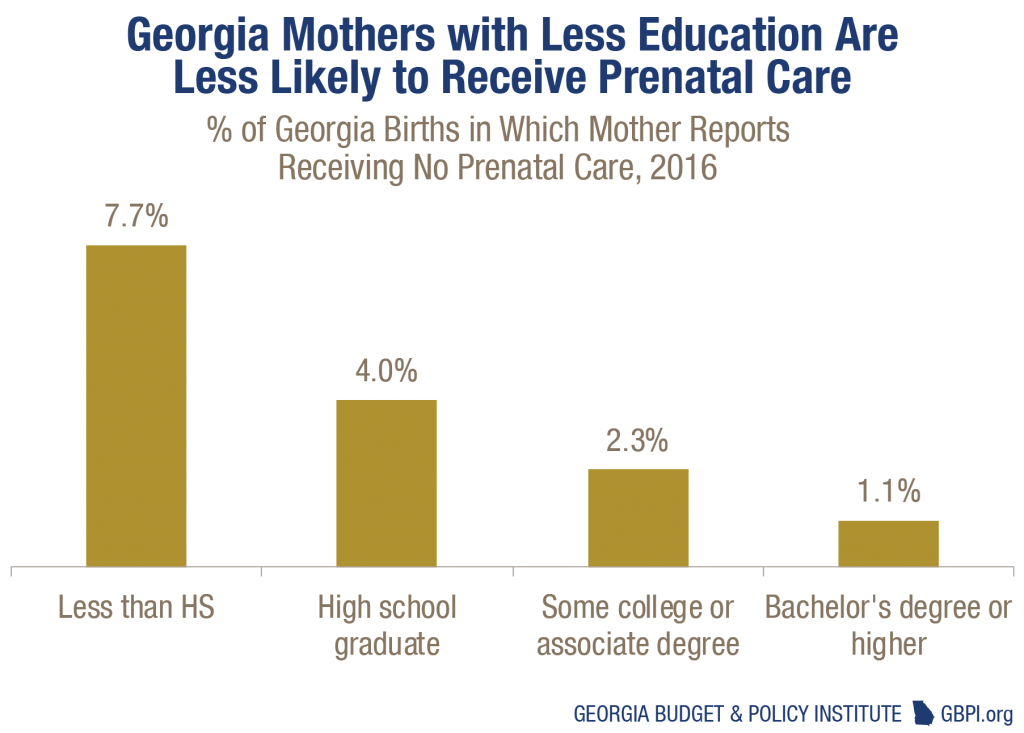

The EITC is associated with higher likelihood of receiving prenatal care, specifically among mothers with a high school education or less.[11] Nearly 8 percent of Georgia mothers with less than a high school education do not receive prenatal care, compared to just 2 percent of mothers with some college or an associate degree.

A refundable Georgia Work Credit can help reduce disparities in prenatal care visits, measured by education and race. Putting more money into the pockets of low-income workers through the credit helps these families afford transportation, health insurance, and health care, all of which gives easier access to prenatal care.

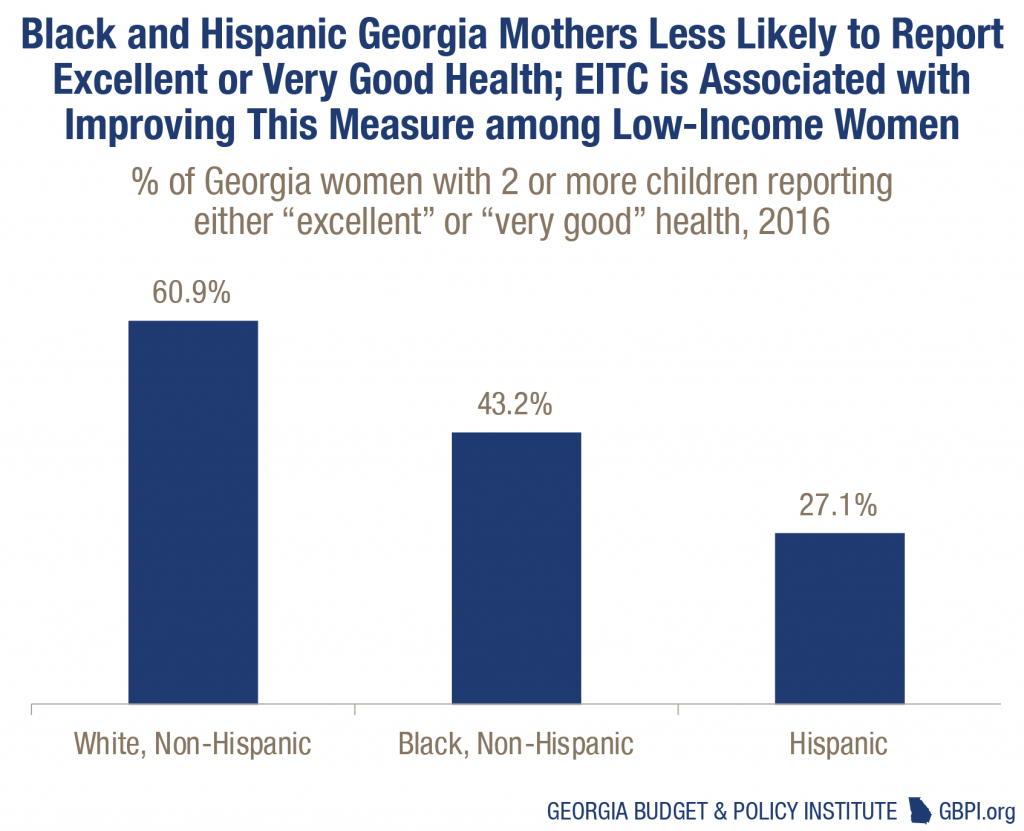

Mothers reporting excellent or very good health

Congress drastically expanded the federal EITC in 1993 to give families with two or more children a greater income boost. Research on the 1993 expansion indicates the larger income gains for bigger families lead to health improvements. Mothers with two or more children who received higher EITC payments increased their likelihood of reporting excellent or very good health by 1.35 percentage points post-EITC expansion, according to a study.[12] More mothers reporting good health not only benefits them but can also play a role in improving child well-being.

Reporting excellent or very good health is a good measure of overall health status. Black and Hispanic women are less likely to report excellent or very good health than white and Asian women. Black and Hispanic women also have lower incomes at an annual average of $32,883 and $25,361 respectively, compared to $41,245 for white women and $40,361 for Asian women.[13] Helping provide an increase in take-home pay through a Georgia Work Credit can provide a boost for Black and Hispanic women who are more often working in lower wage positions and help them access more of the resources they need to have better overall health.

Infant and Child Health

Low birthweight

Georgia is home to the fifth-highest share of newborns with low birthweight in the nation.[14] An infant born weighing less than 5 pounds and 8 ounces is considered to have a low birthweight. Birthweight is an important measure of infant health, since babies with low birthweights have a higher likelihood of suffering more health problems like chronic lung disorders or heart conditions. Some of these complications, such as developmental delays, can affect their health for life. Low birthweight is also a leading cause of infant mortality. Georgia ranks fifth worst measured by infant mortality rates.

Enacting a state EITC is one proven way to reduce the low birthweight problem. Georgia might realize an 8.4 percent decline in low birthweight if the state enacts a refundable EITC at a 10 percent match, according to a 2017 study.[15] This can reduce the number of babies with low birthweight by 1,047 each year in Georgia. More babies born at a healthy weight can help reduce Georgia’s high rate of infant deaths and help more babies grow to adulthood with fewer health problems.

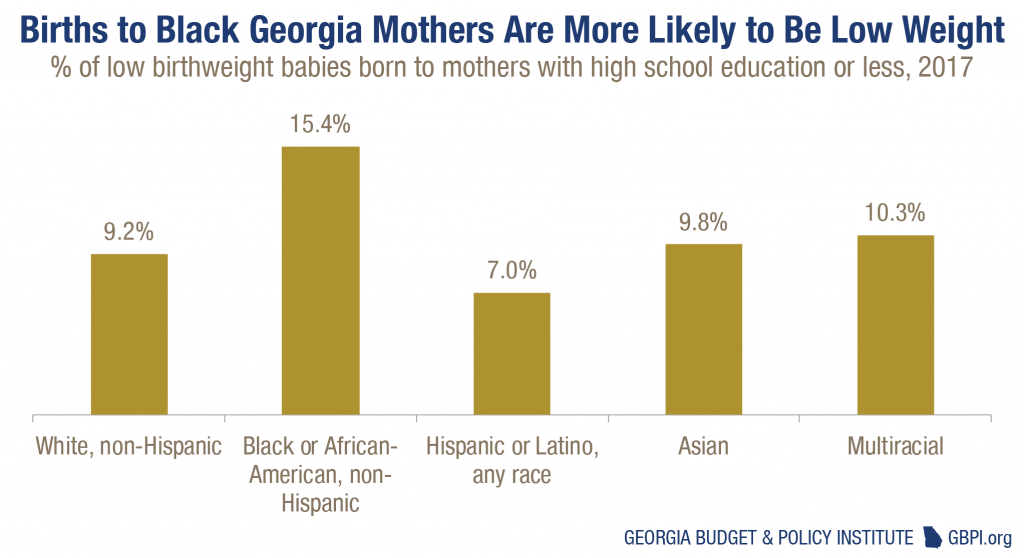

A reduction in low birthweight under an EITC can also help reduce the disproportionate burden of low birthweight among some mothers based on their racial and ethnic backgrounds. Black mothers in Georgia deliver a higher percentage of low birthweight babies than mothers of other races. Expansion of the EITC is associated with a decline in low birthweight among all mothers, but black mothers experience the most improvements.[16] One study of mothers with a high school education or less showed that for every $1,000 increase in the EITC, the instance of low birthweight shrunk by 5.6 percent. Among black mothers, that reduction was 7.2 percent.[17]

Childhood health and obesity

The EITC can help improve children’s health by improving educational achievement and increasing family income, both of which are associated with long-term wellness. Mothers with comparatively larger EITC refunds, in increments of $100, are less likely to report the health of their children ages 6 to 14 as fair or poor and are more likely to report it as excellent.[18]

The EITC can help improve children’s health by improving educational achievement and increasing family income, both of which are associated with long-term wellness. Mothers with comparatively larger EITC refunds, in increments of $100, are less likely to report the health of their children ages 6 to 14 as fair or poor and are more likely to report it as excellent.[18]

In the months where most of the EITC refund arrived, eligible households spent more money on food, with the largest spending increase on healthy and nutritious foods, a study shows.[19] The changes in food consumption help explain some of reduction in childhood obesity associated with the state EITC. Following the adoption of a state EITC, children in non-metropolitan areas experienced larger reductions in obesity rates than children in metropolitan areas.[20]

This suggests that a Georgia Work Credit could provide an outsized benefit to the state’s struggling rural communities, especially considering that taxpayers eligible for the credit tend to account for a larger share of non-metro county residents.[21] Overall obesity rates are higher in the 124 counties that are not part of Georgia’s Census-designated metropolitan statistical areas.

Mental Health

Reported bad mental health days

By providing a boost to the income of working families, the EITC can help reduce some of poverty’s harm to mental health. Living in poverty can include the anxiety of trying to make ends meet and living in an environment that may bring increased exposure to trauma and violence.[22]

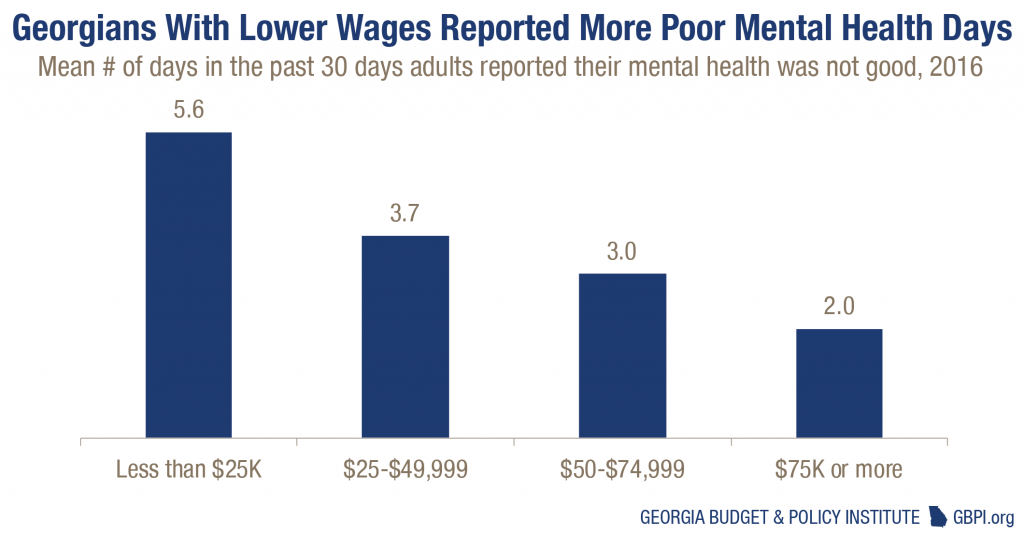

A $500 increase in EITC payments reduced the number of bad mental health days by 19 percent for low-income mothers, a study says.[23] Georgia women and Georgians with lower incomes report more bad mental health days than other groups. Georgia women reported an average of 4.3 poor mental health days, while men reported 3.2 days. The positive mental health benefits of the EITC can help more low-income women in Georgia achieve better health and accomplish their goals. Lowering the number of reported bad mental health days also offers economic benefits. This is especially true for poorer counties with lower median home values, which are often more rural. One bad mental health day is associated with a 2.3 percent reduction in income growth in rural and poorer counties and a 0.87 percent reduction in urban counties.[24]

Children’s behavioral health

About 23 percent of Georgia children lived below the poverty line in 2016.[25] Children living in poverty are more likely to experience physical and emotional stress due to unsafe environmental and housing conditions or family turmoil. Children living in poverty felt more helpless and suffered more deficits in short-term spatial memory as adults, according to a 15-year study.[26]

Increasing the EITC can help working poor families keep more of their wages and work toward the middle class. This can result in positive benefits for children’s emotional and behavioral health. Larger EITC payments are associated with higher scores for children on a behavioral index that includes measures such as peer conflict, hyperactivity, anxiousness and depression.[27]

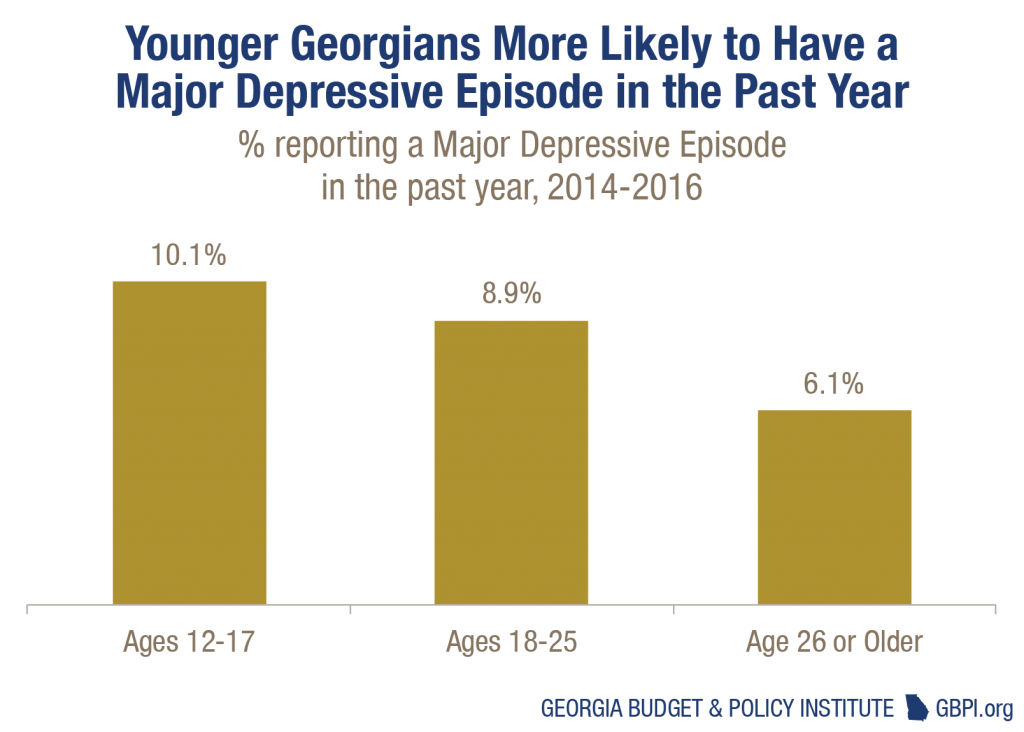

Georgia children ages 12 to 17 were more likely to report suffering a depressive episode in the past year. Investing in the Georgia Work Credit is one way to address the disproportionate mental health challenges Georgia’s youth face. Intervening early in children’s lives through increased family income can deliver powerful long-term improvements to Georgia’s overall health as those young people grow into healthier adults.

Conclusion

Georgia can improve the health of its people by extending the EITC’s poverty-reduction benefits through a state-level version of the tax credit, or Georgia Work Credit. Twenty-nine states and the District of Columbia enhance the value of the federal EITC by also offering a credit that offsets state and local taxes and evidence suggests that benefits include healthier babies and improved mental health for older children. A refundable Georgia Work Credit set at 10 percent of the federal EITC can cut taxes by a few hundred dollars a year for eligible workers, up to around $630 per family, money they can use to purchase healthier foods and reduce money-related stress.

Nearly two in three Georgians support a Georgia work credit, according to a July 2018 Mason Dixon Polling & Strategy survey commissioned by GBPI. The poll of 625 Georgia voters found broad support for the state to offer a tax credit to working families to help them make ends meet and move out of poverty.

Nearly two in three Georgians support a Georgia work credit, according to a July 2018 Mason Dixon Polling & Strategy survey commissioned by GBPI. The poll of 625 Georgia voters found broad support for the state to offer a tax credit to working families to help them make ends meet and move out of poverty.

Georgia lawmakers can strengthen working families and local economies with a state EITC and at the same time can help improve the health of Georgians and promote health equity throughout the state. A Georgia Work Credit enjoys popular support in the state. It is time for Georgia lawmakers to embrace an EITC and join the majority of the rest of the states.

Endnotes

[1] Paula Braveman and Laura Gottlieb, “The Social Determinants of Health: It’s Time to Consider the Causes of the Causes.” Public Health Reports, January-February 2014; 129: 19-31.

[2] Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S. “The Association Between Income and Life Expectancy in the United States, 2001-2014.” JAMA. 2016; 315(16):1750-1766.

[3] Wesley Tharpe. “A Bottom-Up Tax Cut to Build Georgia’s Middle Class.” Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. 2017.

[4] William N. Evans and Craig L. Garthwaite, “Giving Mom a Break: The Impact of Higher EITC Payments on Maternal Health,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. 2014; 6 (2): 258-90.

[5] Hoynes H, Miller D , and Simon D, “Income, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and Infant Health,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. 2015; 7(1):172-211.

[6] Strully, KW, Rehkopf, DH, and Xuan, Z “Effects of Prenatal Poverty on Infant Health: State Earned Income Tax Credits and Birth Weight.” American Sociological Review. 2010; 75(4): 534–562.

[7] Markowitz S, Komro KA, Livingston MD, Lenhart O, Wagenaar AC. “Effects of state-level Earned Income Tax Credit laws in the U.S. on maternal health behaviors and infant health outcomes.” Social Science and Medicine, 2017; 194, 67-75.

[8] Estimates for improvement in birth weight for Georgia were generated by authors of the study Markowitz, et al using data from the National Center for Health Statistics’ Linked Birth / Infant Death Records database for 2007-2014, accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/lbd-current.htm.

[9] William N. Evans and Craig L. Garthwaite, “Giving Mom a Break: The Impact of Higher EITC Payments on Maternal Health,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. 2014; 6 (2): 258-90.

[10] Rita Hamad and David H. Rehkopf. “Poverty and Child Development: A Longitudinal Study of the Impact of the Earned Income Tax Credit.” American Journal of Epidemiology. 2016. 183 (9):775-84.

[11] Hoynes H, Miller D , and Simon D, “Income, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and Infant Health,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. 2015; 7(1):172-211.

[12] William N. Evans and Craig L. Garthwaite, “Giving Mom a Break: The Impact of Higher EITC Payments on Maternal Health,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 16296 (2010).

[13] “Status of Women in the States.” Institute for Women’s Policy Research. 2018.

[14] America’s Health Rankings. United Health Foundation. https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/annual/measure/birthweight/state/GA

[15] Markowitz S, Komro KA, Livingston MD, Lenhart O, Wagenaar AC. “Effects of state-level Earned Income Tax Credit laws in the U.S. on maternal health behaviors and infant health outcomes.” Social Science and Medicine, 2017; 194, 67-75.

[16] Hoynes H, Miller D , and Simon D, “Income, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and Infant Health,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. 2015; 7(1):172-211.

[17] Phineas Baxandall and Monique Ching. “A Credit to Health: The Health Effects of the Earned Income Tax Credit.” Massachusetts Budget and Policy Center. 2018.

[18] Baughman RA and Duchovny N. “State earned income tax credits and the production of child health: insurance coverage, utilization, and health status.” National Tax Journal. 2016; 61 (1), 103-132.

[19] McGranahan L and Schanzenbach DW. “The Earned Income Tax Credit and Food Consumption Patterns.” Working Paper, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, No. 2013-14.

[20] Reagan A. Baughman. “The Effects of State EITC Expansion on Children’s Health.” (2012). The Carsey School of Public Policy at the Scholars’ Repository. 168.

[21] Wesley Tharpe. “A Bottom-Up Tax Cut to Build Georgia’s Middle Class.” Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. 2017.

[22] Reed Jordan. “Poverty’s toll on mental health.” Urban Institute. 2013.

[23] William N. Evans and Craig L. Garthwaite, “Giving Mom a Break: The Impact of Higher EITC Payments on Maternal Health,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. 2014; 6 (2): 258-90.

[24] Davlasheridze M, Goetz S, and Han Y.. “The Effect of Mental Illness on U.S. County Economic Growth.” The Review of Regional Studies, Southern Regional Science Association. 2018; 48(2), 155-171.

[25] United States Census Bureau, Selected Population Profile in the United States: 2016 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates. Data retrieved from talkpoverty.org.

[26] Gary W. Evans. “Childhood poverty and adult psychological well-being.” Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(52),14949–52.

[27] Rita Hamad and David H. Rehkopf. “Poverty and Child Development: A Longitudinal Study of the Impact of the Earned Income Tax Credit.” American Journal of Epidemiology. 2016. 183 (9):775-84.